New research has made it possible to identify a number of unknown World War 2 victims buried in Mayo in 1941 when their bodies were washed ashore following the sinking of the Canadian troopship, S.S. Nerissa, off Donegal.

Because of wartime secrecy, the Gardai did not have access to casualty lists from ships torpedoed off our shores. Thus, the identity of many of the Nerissa victims who washed ashore in Mayo in the early summer of 1941 has remained a mystery for over eight decades.

© Anthony Hickey 2022. All Rights Reserved.

Following extensive research in the National Archives of Ireland by this writer Anthony Hickey for my article The Tides of War – Mayo and The Battle of the Atlantic (1939-45) and, working with Bill Dziadyk, a retired Lieutenant Commander in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), we have been able to shed new light on the fate of four Nerissa victims whose bodies were washed into coves and onto beaches from Donegal to Clare.

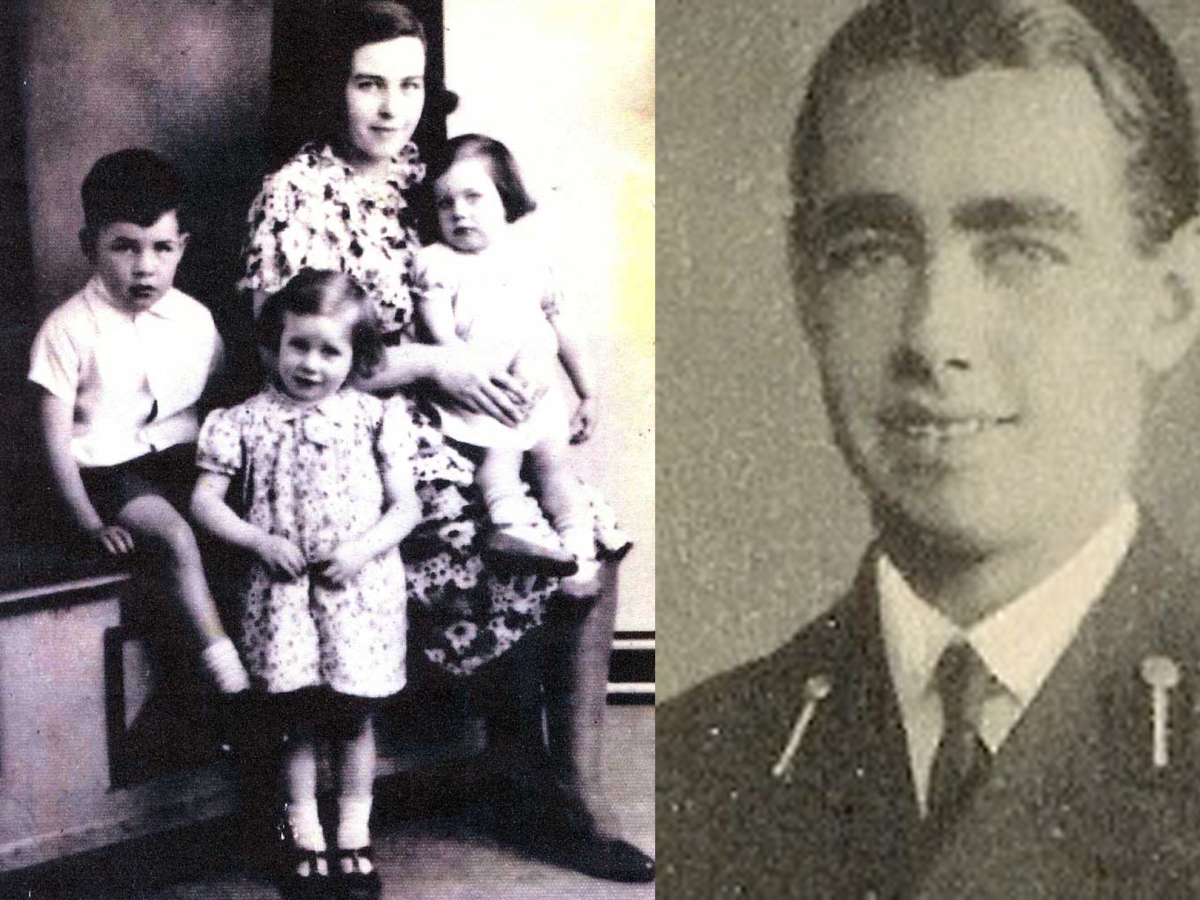

Among the unknowns that can now be identified were a brother and sister, Terence (6) and Joan Lomas (4), the youngest victims to be washed ashore along Ireland’s west coast during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Also identified, over eight decades after his death, is a heroic young Canadian naval officer who in the final terrifying minutes before Nerissa sunk beneath the waves had helped the two Lomas children into a lifeboat.

Sub-Lieutenant Barnett Harvey was just 20 years old when he drowned along with 206 other passengers and crew aboard S.S. Nerissa, bound from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Liverpool. The unescorted steamer sunk within four minutes of being hit by two torpedoes fired by the German submarine U-552 at about 10.30pm on April 30, 1941.

From Courteney BC, Harvey was of Scottish heritage and came from a military family. He found his final resting place in Ballycastle graveyard where his unmarked grave has now been identified and efforts are underway to have his burial place suitably marked.

Lomas Family Tragedy

Harvey’s valiant efforts to save the lives of Joan (4) and Terence Lomas (6) were mercilessly dashed when the U-boat commander Erich Topp fired a second torpedo into Nerissa which capsized the lifeboat in which the children along with their parents, Joseph (31) and Elizabeth (26), and sister Margaret (3), had taken refuge.

Tragically, if the U-boat commander had only fired one torpedo into Nerissa the Lomas family and many others would have been saved along with the 84 others who survived the sinking and were rescued by Royal Navy vessels which brought them to Derry. But the impact of the second torpedo explosion overturned Lifeboat No. 2 into which the family had scrambled with the help of Sub-Lieutenant Harvey. All the occupants were thrown into the sea and perished.

Homesick and unable to settle in Canada after escaping the London blitz in 1940, Joseph Lomas, a carpenter, was bringing his wife and young family back to Charlton where Elizabeth’s mother, Ellen, lived. They were only hours away from safety in Liverpool when they perished.

The Lomas family story is one of the great tragedies of the Battle of the Atlantic; their terrible fate is symbolic of today’s refugees and how the innocent suffer most in war. Their deaths are also a poignant reminder of all the young lives cut short during World War 2’s longest battle.

Like so many victims of the Battle of the Atlantic that were washed ashore, little Joan Lomas had no identification on her body when discovered at Dooyork, a short walk from the beautiful seaside village of Geesala.

Still dressed in the one-piece blue and red pyjama suit, in which her mother had put her to bed, on that fateful night, she was buried in Geesala cemetery where the location of her unmarked grave can be identified following my research.

A memorial headstone has now been erected at Joan’s grave in remembrance of Joan and her family and their great tragedy.

Joan’s brother Terence (6) was also washed ashore in late May 1941 at scenic Kilgalligan beach located between Rossport and Carrowteigue, along with an adult female and an adult male. Terence would have been buried in the nearby Kilgalligan graveyard. The exact location of his grave and that of the two adults is unknown but the plot is likely to be in the north-west corner of the old cemetery where a number of bodies washed ashore during World War 2 were buried. It is also likely that all three were buried together as, at the time, it was assumed they were a family.

Harvey’s religious medals

Historic documents in Ireland and Canada have made it possible to identify the remains as Barnett Harvey, but the finding of his grave in Ballycastle in recent months revealed a remarkable story involving three Catholic medals found on his body when it was discovered washed up on the rocks at Doonfeeney Upper on May 25, 1941, by local man, Thomas A. Heffron.

The religious medals may not have saved Harvey from death in the North Atlantic, but in a strange twist of fate had he not carried the medals on that fateful voyage his grave would never have been located.

Barnett Harvey was an Anglican, but because of the medals, it was assumed in Ballycastle that he was a Roman Catholic and therefore given a Catholic burial in an unmarked plot alongside the graves of the local dead. His burial was recorded in the Ballycastle Parish Register of Interments for May 1941, including an annotation mentioning that it was believed he was a Canadian naval officer.

Without the medals, likely to have been given to him by a Catholic friend as he embarked on a dangerous voyage to war, Barnett Harvey would have been buried in the so-called “Strangers’ Plot”, a corner reserved in cemeteries in times past for the burial of unknown persons and the unbaptised. This is where most of the bodies washed ashore in Ireland during the war were buried. The location of these unmarked graves in most cases is no longer known. Those who could be identified, mainly military and a small number of merchant seamen, were later given Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones.

From late May to July 1941, bodies from S.S. Nerissa came ashore along the west coast, including two military officers, Archibald Graham Weir (55), a Wing Commander in the RAF, and Canadian Officer, Thomas Elvin Mitchell (20), a Lieutenant in the Carleton and York Regiment, R.C.I.C. Both were found on the Mullet peninsula and buried in the Belmullet Church of Ireland churchyard.

The Master

In Achill Sound Church of Ireland’s graveyard, there are 13 Commonwealth War graves all related to the Battle of the Atlantic. One of those headstones remembers “A Master”, whose body was washed ashore at Ashleam, Achill Sound, on June 28, 1941. As a result of our investigations, we believe that compelling evidence exists to suggest that this was Gilbert Ratcliffe Watson, the Master of S.S. Nerissa.

Our historical investigations have also uncovered evidence that another unidentified Nerissa victim was washed ashore on the strand at Carrowmore, Doonbeg, County Clare, on May 29, 1941.

The body of Ordinary Telegraphist James Hutton was interred in an unmarked grave in Clohanes Cemetery. Work continues in trying to find his grave and have it suitably marked.

Our research has also established that the bodies of two of the four adult females on Nerissa came ashore in Mayo and there is no evidence of either of the two stewardesses’ bodies coming ashore. As stated earlier, an adult female was found near the body of Terence Lomas at Kilgalligan. Analysis of the available evidence strongly suggests that this was Elizabeth Lomas.

I have been unable to locate documents in relation to the Kilgalligan bodies in the National Archives which would likely have indicated whether or not this was Elizabeth Lomas. The file in relation to the finding of these bodies is likely to have been lost as also appears to have happened in a number of other cases.

But I believe it is not unreasonable to imagine that in those final terrifying moments, a mother would have held onto one of her children; and for any relatives, there is some small consolation in believing that she was buried with her child in the remote Mayo cemetery overlooking the beach where they came ashore.

There is only a remote possibility that the remains of the man washed ashore at Kilgalligan were those of Joseph Lomas as the great majority of the 207 Nerissa casualties were adult males.

Second Woman

The body of a second adult female came ashore at Grangehill, Barnatra, (near Belmullet) at about the same time, May 23, 1941. National Archive documents suggest on the balance of probabilities that the body was that of recently married Joy Stuart-French (35), born Vida Joyce Jones, from Warracknabeal, Victoria, Australia. She was the wife of Major Robert Stuart-French (11th Hussars), a native of Cobh, Co. Cork. His ancestral home was the Marino House Estate, between Rushbrooke and Fota in Cork Harbour where his parents lived until their deaths in the 1950s. The woman’s remains were buried in Termoncarragh cemetery on the Mullet peninsula where I have been able to identify the location of her unmarked grave.

There were just two stewardesses on Nerissa – Florence Jones (50) and Hilda Lynch (34), both from the greater Liverpool area. The courage and sacrifice of the two stewardesses on Nerissa should not be forgotten.

In the madness and panic, as Nerissa began to sink quickly, the two brave women gave their lifebelts to the two older Lomas children and unflinchingly accepted their fate.

Lifebelts were found near both the bodies of Joan and Terence Lomas when they were found three weeks later at Dooyork and Kilgalligan; almost as if the spirits of the two brave women had brought their little bodies ashore.

Tragedy of Lomas family remembered in Geesala

In early June 2023, a memorial headstone was erected over the grave of four-year-old Joan Lomas in Geesala in remembrance of the tragedy of the Lomas family. All the work on the grave was carried out on a voluntary basis.

I would like to thank Michael Feeney of the Mayo Peace Park for all his support and encouragement in helping to bring this project to fruition.

In early May 2023, Michael Feeney and I, along with a number of other long-standing members of the Mayo Peace Park Committee, namely Ernie Sweeney, John Moran, and Peter Foran developed and prepared the grave in Geesala for the headstone.

Great thanks are due to Hugh Ginty of G. Ginty and Sons, Monumental Sculptors, Ballina, and Castlebar, for their generous sponsorship of the memorial.

The support of Roadstone, Castlebar, is also greatly appreciated.

In early June 2023, I made contact with a first cousin of little Joan Lomas.

Memorial Inscription

The inscription on the Lomas family memorial in Geesala graveyard includes two lines in Gaelic from an Irish hymn translated below:

In Loving Memory of

Joan Lomas

Aged 4

Charlton, London

Died April 30 1941

Sinking SS Nerissa

Along With

Her mother Elizabeth, Aged 26, and brother Terence, Aged 8

Interred in Kilgalligan

Her father Joseph, aged 31 and sister Margaret Aged 3,

Lost at Sea

Ag Críost an mhuir, ag Críost an t-iasc;

líonta Dé go gcastar sinn.

(Christ of the Sea, Christ of the Fishes

In the nets of God we may be found)

Our Evidence

In our analysis, we were able to consider the wartime context when the bodies washed ashore, which 80 years earlier, the Gardai did not know because of wartime secrecy.

For those who would like to read Bill Dziadyk’s meticulous presentation of the new information please click on this link where you will find a copy of a related Addendum which was published in an update to his book, detailing what we have uncovered; and the analysis and evidence provided by Bill Dziadyk and myself.

Bill Dziadyk’s book – “S.S. Nerissa, the Final Crossing: The Amazing True Story of the Loss of a Canadian Troopship in the North Atlantic,” – is the definitive account of the S.S. Nerissa and tells the final dramatic journey of the steamer, including the personal stories of many of its ill-fated crew and passengers.

Postscript

Work continues to try and find the surviving next-of-kin of the Nerissa victims buried in Mayo and in Co. Clare.

Therefore, all publicity arising out of this story is welcome as it might alert any surviving family members to the new information regarding their relatives.

Acknowledgments

Research like this cannot be completed without the help and support of other people and one such man is John Bourke of An Siopa Suifinn, Main Street, Ballycastle, without whom we might never have been able to locate the grave of Sub-Lieutenant Barnett Harvey.

I would also like to thank William Winters of Winters Jewellers – The Hazel, Ballina, for his expertise as a jeweller in helping to identify the wedding ring in the case of the adult female found at Grangehill, Barnatra.